I’d like to talk about a problem. It might seem like quite a small problem, but it’s a pervasive one. That problem, is salad.

Yes, that’s right, I said salad. Not high on the list of major world perils, but perhaps it should be. I mean, for starters, it’s everwhere. Lurking in every supermarket-bought sandwich, mocking you from the side of every pub lunch, withering beneath every take-away spring roll. And that sad bit of salad that came with your meal, that you never even for a moment considered eating, has caused a surprising amount of damage to the environment.

Never has so much fuss been made about a piece of food that the majority of people don’t even touch. I wanted to find out just how bad for the environment lettuce really is.

The Water Footprint of Salad

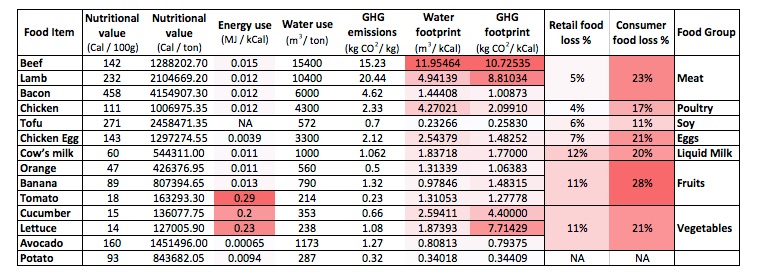

I did my research and I tracked down estimates of the nutritional values of lots of different types of food, and the latest stats on their water consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, and .

Lettuce is almost entirely water, but it’s got virtually no nutritional value at all.

Not surprisingly, beef is off the scale in terms of water use and GHG emissions. We knew that. What surprised me was that beef wasn’t the worst for energy use – in fact, salad was! Tomatoes, cucumbers and lettuce all use an order of magnitude more energy per calorie than any of the meats. While that might not justify switching to that all-steak diet you’ve always dreamed of, it does remind us that salad can be just as bad, if not worse, in terms of environmental cost versus nutritional value. Water use and greenhouse gases were higher for lettuce and cucumber than any of the other non-meat items on the list, and considerably worse per-calorie than bacon.

So the lettuce in your BLT might actually be worse for the environment than the bacon.

All this water consumption comes at a cost. In parts of California, the demand for water to grow lettuce and broccoli, combined with historic droughts, is crippling the limited groundwater supplies. Some farmers have responded by switching to “dry farming” – relying on rainwater rather than artificial irrigation and working the soil to maximise nutrients. Many fruits and vegetables can be grown in this way, but predominantly water-based salad fillers like lettuce and cucumber may never taste satisfactory if grown with these methods.

Lettuce production is also particularly bad for the environment – requiring 11 pesticides on average (more than any other vegetable crop), and in many areas requiring large amounts of nitrate fertiliser to grow. Excess pesticides and fertilisers are inevitably washed into nearby streams by the rain, and leach into the soil, poisoning far more than their target pests.

Wasted Salad

And then we go on and waste a huge amount of the salad we produce. And I’m as guilty of this as anyone. I never order salad in a restaurant, but it’s always there. It’s like the surrepticious straw in your gin and tonic – there before you thought to say you didn’t want it, and a complete and utter environmental catastrophe. Portion sizes have increased between 70% and 400% since the 1980s, but as well as rising obesity levels, larger portions have also meant more waste. The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United States (FAO) estimates that globally, around one third of the food we produce for human consumption is wasted – roughly 1.3 billion tonnes, and fruit and vegetables are the most wasted.

Half of all root crops, fruits and vegetables grown are never eaten.

Much of this waste occurs at home – roughly 40% in industrialised countries – we buy fruit and vegetables without a specific meal or occasion in mind, and even the best meaning of us occasionally forget, leaving it to wilt in the salad draw.

According to a recent survey by Tesco, the British public waste 40% of bagged supermarket salad – that’s not even taking into account all the unwanted side salads that contribute to commercial food waste.

We also waste a huge amount of salad in restaurants. One study in a student-run restaurant in Guelph, Canada, found that on average 8% of the food served on the plate gets wasted.

Food losses contribute 1.4 kilograms of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each day towards the GHG footprint of the average U.S. diet.

Part of a balanced diet

Of course nobody is getting all their sustenance from just one type of food, so it’s important to evaluate whole diets rather than individual food stuffs.

In a study at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, USA, researchers reported that were the average American to shift their diet to meet the USDA recommended dietary guidelines, they would increase their environmental impact considerably – increasing energy use by 43%,

In a study at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, USA, researchers reported that were the average American to shift their diet to meet the USDA recommended dietary guidelines, they would increase their environmental impact considerably – increasing energy use by 43%, consumption by 16% and greenhouse gas emissions by 11%. Even though it represented a reduction in calories (the average American apparently consumes nearly 2400 calories a day), this dietary change would cause a greater environmental impact because of the increased contribution of fruit and vegetables – together the first and third most energy intensive foods in their study.

Another study compared four common diets in the EU – the average diet between 1996 and 2005; a healthy diet as defined by the German nutrition society; a healthy vegetarian diet, and a combination diet, replacing half of the meat with pulses and protein alternatives. They found that most of the total water footprint of each diet was due to agricultural goods, with 46% due to animal products and 37% due to crops.

Switching to any of the healthy diets improved water consumption, but reducing meat, oil and sugar consumption had the largest effect. The vegetarian diet had the lowest water footprint in their study, primarily due to relatively high water demands of producing milk. But milk isn’t the only culprit – milk alternatives like soy milk are also very water intensive. It takes 297 litres of water to make 1 litre of soy milk, mostly due to the water-intensive production of soybeans. Looking at greenhouse gas emissions, Americans switching from the current average to the recommended diet would cause a 12% increase in GHG emissions. This could be almost entirely ameliorated, however, by reducing the calorie intake from 2500 to 2000 calories per day.

Using more basic, raw ingredients and cooking from scratch can also make a big impact – processed foods take more water, energy and emit more greenhouse gases than simpler products and raw ingredients, a factor that often isn’t taken into account.

Environmentalists spend so much time and energy trying to convince people to eat less meat and reduce their environmental impact, and that’s great, but I feel like we’re missing the low-hanging fruit and veg. Fundamental dietary changes take a lot of time and effort, but cutting out something most of us aren’t even eating anyway seems like it should be pretty easy. I think what frustrates me is that we’re missing some of the simplest and most obvious lifestyle changes, changes that we’d barely even feel, but because of their scale could have a significant impact.

It’s time to put an end to superfluous salad. #saynotosalad

Putting an end to unnecessary food waste like salad is actually relatively simple, but it requires a change of attitude. For instance, in Denmark, public pressure has led to successful campaigns, like convincing supermarkets to switch bulk discounts for single-item offers, and a surplus food supermarket to make better use of the country’s 700,000 tonnes of food waste each year.

If we stop expecting decorative side salads in bars and restaurants – if we stop being complacent and start being outraged, then businesses will be forced to respond and reduce waste. And when they do, they’ll be pleased to notice that their profits go up.

We can make win-wins for sustainable initiatives if we exert our consumer power and make it clear that these issues matter to us, the consumers.

I can’t live without salad!

If you’re someone who actually eats and enjoys salad, here’s some great tips on how to grow your own.

And if you do find yourself with unwanted salad on your hands, please dispose of it in an environmentally responsible way. You might have heard that throwing food waste such as salad into the landfill waste is OK because it’ll naturally decompose, but it’s not that simple. Bagged salad in a landfill, buried beneath other bags of mixed waste, decomposes without access to oxygen, producing large quantities of the green house gas methane. In contrast, waste salad that’s placed on a compost bin (which should be turned over regularly) can decompose aerobically (in the presence of oxygen), avoiding those extra emissions. Taking the time to put waste salad into your food waste collection or home compost bin really does make a difference.

Want to know more?

- Tom, M. S., Fischbeck, P. S., & Hendrickson, C. T. (2016). Energy use, blue water footprint, and greenhouse gas emissions for current food consumption patterns and dietary recommendations in the US. Environment Systems and Decisions, 36(1), 92-103.

- Heller, Martin C., and Gregory A. Keoleian. “Greenhouse gas emission estimates of US dietary choices and food loss.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 19.3 (2015): 391-401.

- von Massow, Mike, and Bruce McAdams. “Table Scraps: An Evaluation of Plate Waste in Restaurants.” Journal of Foodservice Business Research 18.5 (2015): 437-453.

- Hall, G., et al. (2014) Potential environmental and population health impacts of local urban food systems under climate change: a life cycle analysis case study of lettuce and chicken. Agriculture & Food Security 3(1),6

- Lipinski, Brian, et al. (2013) “Reducing food loss and waste.” World Resources Institute Working Paper.

- Vanhama, Mekonnen and Hoekstra (2013) The water footprint of the EU for different diets. Ecological Indicators 32, 1–8

- Stoessel, Juraske, Pfister, and Hellweg (2012) Life Cycle Inventory and Carbon and Water FoodPrint of Fruits and Vegetables: Application to a Swiss Retailer. Environ Sci Technol 20; 46(6): 3253–3262.

- Ercin, A. Ertug, Maite M. Aldaya, and Arjen Y. Hoekstra (2012) “The water footprint of soy milk and soy burger and equivalent animal products.” Ecological indicators 18: 392-402.

- Mekonnen, M.M. and Hoekstra, A.Y. (2011) http://waterfootprint.org/en/resources/water-footprint-statisticsThe green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 15(5): 1577-1600

- FAO (2012) “SAVE FOOD: Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction“.

- USGS Water Science School – Livestock water use

- GRACE Communications foundation – The Water Footprint of Food